Feast or Famine: Food and Ritual in World History

"For it is in the holy offering of wine and in the revels of feasting that the spirit of the gods dwells among mortals." — Euripides, "The Bacchae"

Food, the most primal of necessities, occupies an area that far surpasses its biological imperative. It is the artillery that binds human experience, a language spoken without words, a tableau of fortune, spirituality, and survival. From the offerings at Olympian symposia to the famine narratives, food—or its absence—has perennially mirrored the desires, fears, and hierarchies of humankind. To dine, abstain, or starve is, historically, to affirm one's place in the cosmos.

Let us indulge, then, in a grand exploration of food as a symbol and ritual—a lens through which to determine the elaborate choreography of culture and power.

Feasts in Myth and Religion

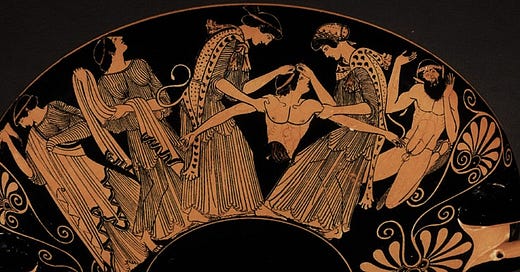

The act of feasting is as old as storytelling itself, an undertaking of divine favor or heavenly celebration. Ancient Greece, for instance, glorified this concept in the symposia—settings not simply for consumption, but for philosophical discourse and the support of societal stratification. These gatherings were suffused with ritual: libations poured for the gods, the willful sequencing of food and drink, and the recitation of poetry. Even the very ambrosia and nectar of their myths suggest that nutrition is sacred, the region of gods and heroes. (If anyone is interested, I can write an article about this also.)

Beyond symposia, we might delve into the rituals tied to specific deities. For instance, the “Eleusinian Mysteries” dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, where grain offerings symbolized death and rebirth cycles, deepened communal bonds, and declared agricultural centrality in Greek life. Similarly, the practice of kapeleia, meaning tavern feasts, (Attic Greek κάπη (kápē): crib, manger = Latin caupō: innkeeper = kapelos (κάπηλος) → kapeleia) in Dionysian festivals reflected the god’s association with wine and liberation from societal norms.

In the icy halls of Valhalla, the Norse divined an eternal banquet, a realm where slain warriors drink mead from the udders of Heidrún and dine on the ever-renewing boar, Sæhrímnir. Here, food became a disguise for bravery—a fellowship of strength and deathless glory. The symbolism of this endless feast extends beyond very indulgence; it reflects an ethos where bravery and sacrifice are rewarded with eternal bond and abundance.

Further afield, in Hindu tradition, festivals like Pongal illustrate how offerings of rice and milk become acts of devotion and gratitude. The preparation and sharing of prasadam (food blessed by a ritual) blur the lines between the mortal and the divine, transforming the act of eating into a sacred communion. The preparation of Panchamrita (a mix of milk, honey, ghee, sugar, and yogurt) for temple offerings is soaked in symbolism—each ingredient representing health, prosperity, and spiritual purity. In this context, food is a bridge between the material and the spiritual realms.

Food as Spiritual Discipline

If feasts are the language of abundance, fasting is its reflective counterpoint. Across religious traditions, the restrain from food has functioned for purification, enlightenment, and spiritual discipline.

Medieval Christianity viewed fasting as an ascetic’s path to purgation, a gesture of humility before God. Lent, with its strict denial, demanded contemplation—a hunger not of the body but of the soul. In many monastic orders, the strict regulation of diet was an affirmation of divine order. Even the preparation of food was invested with ritual significance, with monks often laboring in silence to enable an atmosphere of prayer.

In Islam, Ramadan sanctifies the fast as both personal sacrifice and collective renewal. To abstain by day and feast by night binds the faithful in a shared rhythm of discipline and celebration, emphasizing the fragility and interconnectedness of existence. The suhoor meal before dawn and the iftar at sunset reflect deep communal bonds. The symbolic breaking of the fast with dates echoes the Prophet Muhammad’s own tradition, investing the act with historical resonance. The iftar meal, though modest, becomes a powerful expression of community and gratitude, bringing together families, neighbors, and even strangers.

Buddhist monasticism takes this strictness further, with dietary simplicity echoing its central tenets of detachment and mindfulness. To eat in measured moderation is, in effect, to confront the impermanence of life itself. The mindful preparation and consumption of food—free from desire or distraction—become exercises in spiritual clarity, reflecting the complex interplay of sustenance and tranquility. In Theravāda Buddhism, monks stick to charity rounds, receiving food as goodwill and practicing gratitude. Meals are consumed mindfully before noon, a deliberate act of detachment from cravings. This stark routine highlights the impermanence of pleasure and material dependence.

Politics and Prestige on the Plate

History is filled with instances of feasts utilized as tools of dominance. Royal banquets of Medieval Europe were theatrical declarations of status—an extravagance choreographed to demoralize rivals and inspire amazement. The coronation feasts of English monarchs, for instance, were less about nutrition and more about sensation. Exotic spices, golden tableware, and processions of roasted peacocks in their plumage were not only culinary choices but statements of authority.

The Ottoman Empire, with its sprawling Topkapı kitchens, elevated this to an art form. The kitchens themselves—a labyrinth of specialized stations—were symbolic of imperial order and abundance. Feasts within the palace were orchestrated to convey the divine order of the Padishah or the Sultan, with dishes often layered in symbolism. A particular favorite, pilav (rinsed rice first cooked in butter, secondly boiled in equal amounts of water, then let sit until it soaks all the liquids. This results in a pilaf that is not sticky and every single rice grain falls off of the spoon separately with a flavor that is both sweet and salty.), could feature a detailed balance of flavors that mirrored the empire’s diversity. These kitchens prepared meals for thousands, showcasing imperial efficiency. Beyond the food, the representation was symbolic—minced lamb stews hinted at refinement, while the mass preparation of pilav emphasized conformity. Specialized guilds, like the Janissary cooks, strengthened hierarchical order within this culinary ecosystem.

In Ancient China, banquet diplomacy—particularly during the Zhou and Tang dynasties—played an equally strategic role. These gatherings cemented alliances, their culinary luxuries emphasizing the empire’s reach and resourcefulness. A Tang-era banquet, with its multi-course presentations, often served as a political message: the empire’s granaries were full, its regions secure. Seasonal foods were selected to align with yin and yang principles, supporting harmony within the emperor’s court. Banquets like the “Grand Feast of All Souls” also celebrated the ancestors.

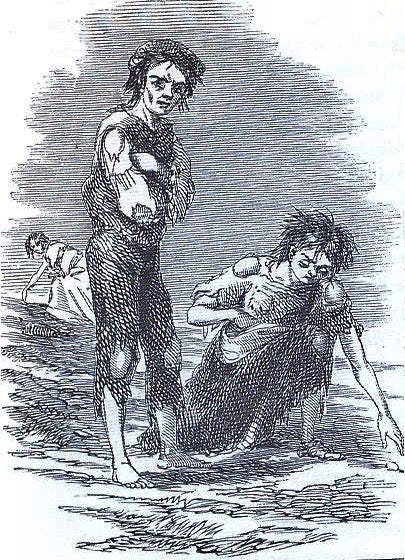

The Ritual of Famine

Well, if feasting represents divine abundance, famine often serves as its intimidating antithesis. “The Great Famine of Ireland” left an indelible scar, its devastation reinterpreted through mythology and cultural memory. Tales occurred of ghostly figures and cursed lands, framing or reframing the scarcity of food as both a tragedy and a cautionary tale of human foolishness. Beyond its immediate devastation, the famine’s legacy reshaped Irish identity. The mass emigration that followed birthed a diaspora whose cultural memory immortalized suffering in folk songs like Skibbereen. Famine stories often summoned blame—on absentee landlords or divine will—connecting hunger to moral dimensions.

In Japan’s Edo period, rice rationing took on a quasi-moralistic tone, remembering Confucian ideals of governance and control. During periods of scarcity, rice became more than a staple; it was a measure of virtue and discipline. The rituals surrounding its distribution—recorded and executed—emphasized the role of the state as the guardian of the people’s interest. The famine of the Boshin War inspired a revival of traditional communal granaries (kura). These measures highlighted, as we’ve mentioned above, the Confucian governance ideals, where local rulers took responsibility for securing care. Rituals of measuring and spreading rice became acts of moral responsibility.

Even within the Bible, famine functions as both divine punishment and crucible. Consider Joseph’s stewardship during Egypt’s seven lean years: an allegory of spiritual practice. Famine narratives often depend on themes of redemption, highlighting the transformative power of deprivation. Famine in the story of Elijah and the widow of Zarephath becomes a test of faith, with a jar of flour and jug of oil miraculously maintaining life. Such episodes stress the divine-human interplay, where scarcity tests virtue and food confirms covenantal faith.

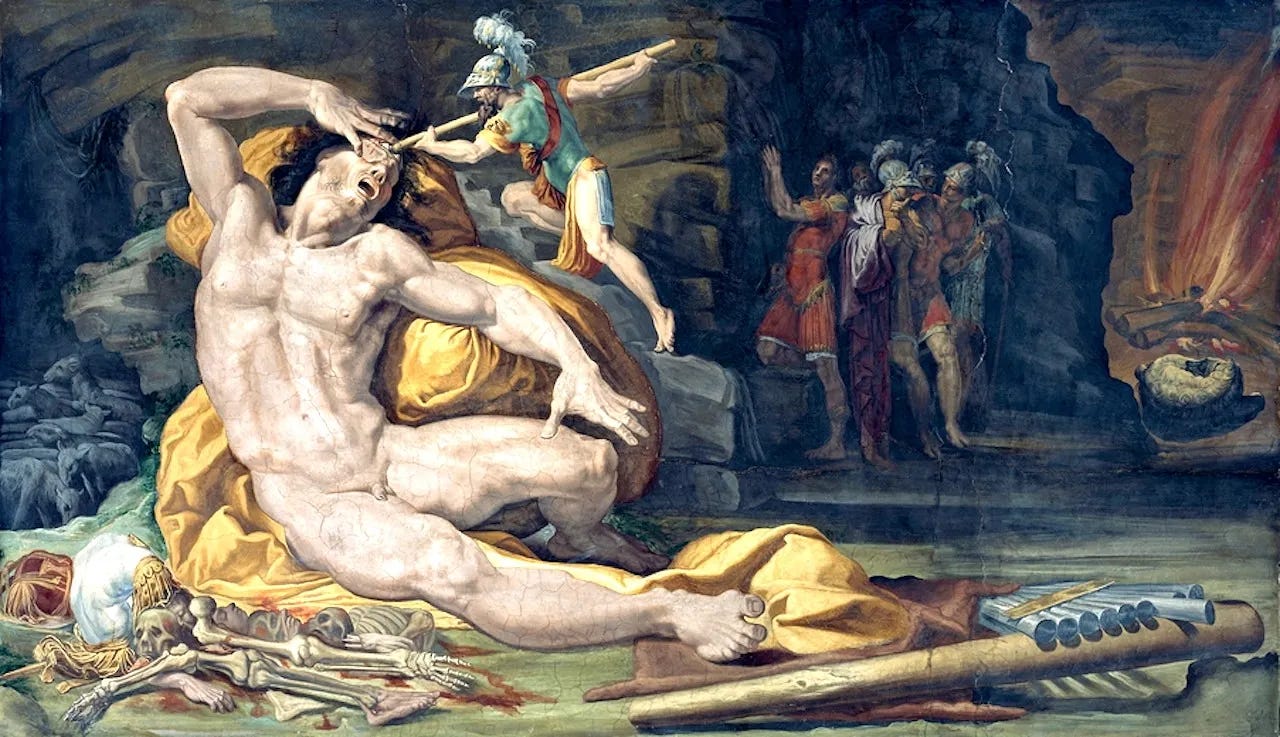

A Taste of Humanity

In literature, food continually serves as a metaphor for human folly or grace. Homer’s epics juxtapose the civilizing effect of feasts with the savagery of their absence. In “The Odyssey”, the ordered hospitality of the Phaeacians contrasts starkly with the barbarism of the Cyclops’ lair, where food consumption borders on cannibalism. Food, in these narratives, draws the boundaries between culture and chaos. Consider the suitors in The Odyssey—their lawless gluttony within Odysseus’ home is a moral failing that contrasts sharply with Penelope’s restraint and loyalty. Food in Homer often conveys hospitality's boundaries, with feasts signaling order and misappropriation symbolizing chaos.

Chaucer’s pilgrims provide another illustrative lens. Beyond individual appetites, the pilgrimage as a journey also manifests through shared meals, which promote companionship while displaying personality. The Miller’s ribald humor, the Prioress’s delicate morsels, and the Franklin’s epicurean generosity all stress the social tapestry that dining creates. Meals in The Canterbury Tales often reflect moral and social manias, blending food with storytelling. Feasts, humble or grand, become microcosms of medieval society, their rituals loaded with meaning.

But what is food if not the narrative of humanity writ small? A thread that weaves itself through myth and history, power and poverty, the heavenly banquet and the humblest crust of bread? These narratives, if I may, in their cacophonous community, remind us of this simple truth: to eat is to participate in life’s constant, messy, and glorious drama.

And so, let us end as we began: with a reflection upon the table, that ancient stage where we perform our weaknesses and virtues. Every feast and famine, every fast and indulgence, every taste and memory—each is a note in the magnific symphony of our existence. To consume is to remember; to savor is to confirm. And as we raise a final glass to this ritual of maintenance, let us do so with the awareness that in every bite lies the world entire—its joys and sorrows, its hungers and hopes, its brief beauty and eternal mystery.

As all things must, we have arrived at the end of this article, and I am compelled to share with you some rather unfortunate news. It seems that Stripe has decided that my association with their enterprise must now come to an end. No reasons were given, no explanations offered to me—as silent and immovable as a marble tomb. Yet, alas, that is a burden I shall bear alone.

More importantly, what concerns us here is not the closing of one door but the opening of another. I am pleased to announce that I have made memberships available on my Buy Me a Coffee account, a platform where generosity flows easily. Supporting my work is now simpler than ever, whether with a one-time contribution starting at a modest $5, or by joining as a Guardian of the Printed World for a monthly membership beginning at $10.

Your generosity sustains the scholarship and vocation to which I have devoted my life. To those who choose to walk this path with me, my deepest thanks—for your kindness is not merely a gesture, but a foundation upon which I build my craft and continue to explore the boundless world of ideas. Here are the details with a URL to my page:

Traditional or ritual, food is entertainment in one hand and the other is fuel. History shows us that. Thanks for the read. You gave me insight. Happy holidays.

Rice pilav is, by far, my favorite side dish.